English | Sri Lankan

I identify as mixed-race, gay and not religious. My mother is from a sleepy village in Norwich, UK, my father is originally from the northern tip of Sri Lanka, having emigrated to India at a young age. My father spent most of his life roaming around India and Nepal bouncing from various different professions and lifestyles, including living in an ashram, before eventually settling in Goa, where he lived a very humble existence. My mother left the UK in the 80s for Australia, having previously backpacked there and fallen in love with the country. They met in a chance encounter on the beach in Goa, my mother backpacking alone around India and my dad always striking up conversations with tourists. Within three weeks, they were married, something which was extraordinarily taboo at the time. White men were able to take Asian wives, but the reverse was rare and deemed controversial. An Asian man was ‘betraying the culture’ if he fell in love with a White woman. Not long after the makeshift wedding, my father returned to his small hut which housed all his possessions to see it had been burnt to the ground. My parents left Goa soon after, traversing Thailand before eventually settling back in Sydney, Australia. I was born a few years later.

I was born in Sydney, Australia. Shortly after my birth, my mother was offered an opportunity to move to San Francisco for work, and, never one to turn down an adventure, her and dad gathered their belongings and zipped off to California, infant Alex in tow. We lived there for three years before returning to Sydney, America never quite felt like home for my parents. I spent the vast majority of my life there. During my formative years we moved to the Northern Beaches, one of the whitest parts of Sydney, and I spent my adolescence and early adulthood there before travelling the world, eventually settling here in London.

I spent a lot of my youth confused by the barrage of terminology that came my way. There are swathes of my life that are tied together by a certain label. When I was in high school, a time when labels are suddenly paramount, I considered myself biracial. It's possible that the term itself was just in vogue, rather than me feeling any particular affinity towards it. As I passed through university, I clumsily appropriated 'Brown', I think in a self-involved attempt to be political. As I've transitioned into adulthood I've settled on 'mixed-race' and being a 'POC'. When I look back I realised that this unwavering truth, that my heritage was 'mixed', has always been at the heart of all of these chosen labels. I can't remember a time when I wasn't aware that I existed in a sort of in-between, not quite one, not quite the other, but impossibly - and miraculously - both. In many ways I think it's been a large force in the formation of my character, my values, and how I navigate the world. To be constantly in between gives you a rare sense of perspective. A perspective which I genuinely believe can change the world.

British and Australian cultures do have considerable differences - which I've been soberly reminded of now that I live in London. Growing up though, they sort of bled into each other, to the point where I always just thought of Britain as a stuffy, self-important, colder Australia. Ultimately, they always felt like close cousins. This couldn't be said as much for Indian or Sri Lankan culture – it's based around different societal norms, a radically different subset of languages, a complex caste and class system, and a whole different palette of melanin. Essentially, my dad always had the odds stacked against him when it came to defending his culture in our family and in our lives. Nevertheless, both of my parents made a concerted effort to never have South Asia too far from their children's minds, often through small gestures. They even – perhaps longingly – named my sister India. We very often ate South Indian food, we had furniture and knick-knacks from that part of the world, we talked about and practiced yoga and meditation. My parents worked hard to afford us an education in which we learnt about the Bhagavad Gita and were taught Sanskrit. As a teen, my parents uprooted me and my sister to see the place of their first encounter in Goa, meet my father's relatives, and see the countries which made up an intrinsic part of our identity. It felt okay – strange more than anything – but it didn't feel like coming home. In any case, my parents persisted, and continue to persist. I know intellectually that I am Sri Lankan. I just don't always 'feel' it.

I think there comes a point in many mixed-race people's lives where the feeling of being in a constant state of in-between begins to take its toll. In a world where our identity – in particular our cultural background – intermingles so dangerously with the opportunities we're afforded, many of us experience a sort of listlessness brought about by sustained othering, without a vehicle through which to express it. Being mixed-race in some ways forces a choice on you, the two halves that make up my whole, the person as I am, has no culture attached to it. So, if I want an avenue through which to express my identity, I have to actively integrate. So many of us integrate – sometimes without even realising it – into a culture which isn't quite our own. The problem is we never fit in. Even though we feel that we may. Not fitting in is an inherent part of who we are.

I look back and I wish that I grew up with the feeling that the experience of being mixed had its own culture attached to it. Its own set of norms. I did occasionally come across other mixed or 'ethnically ambiguous' people and find myself overwhelmed with the similarities of our experience, despite often sharing very few recent genetic ancestors. But these experiences were rare, and fleeting. Growing up, I very rarely knew what it meant to truly 'belong'. This wasn't helped by being gay, another experience in which I was consistently othered or held at arm's-length from society.

The other challenge I always faced was how I dealt with racism. I always felt frustrated that although I was often the victim of it, I had no-one around me that I could share it with who would fully understand. My mother would placate me, and my father would nod knowingly, but the flavour of racism he experienced was different. It was explicit, palpable, seething. What I experienced was covert and quiet. It took me a long time to recognise and acknowledge this constant othering as a pernicious form of racism, one that stings just as much as any other. It took me a long time to 'own' my experience of racism. I denied myself victimhood for a long time. I'm only just coming into my own, acknowledging this part of my life, and re-framing my experience as someone who battled through it and came out the other side stronger.

I struggle to make friends who don't have a lived, or very sympathetic, understanding of what it means to be a person of colour, a queer person, or anyone else who is systemically persecuted. These aspects of my identity have taught me so much and continue to deeply affect how I navigate the world, that I find it hard to connect to people who don't ‘get it’. I've been lucky enough to travel across the world, and I find that a lot of my international friends come from cultures in which mixed heritage is more of a given. Colombians, Mauritians, New Zealanders ...people for whom being mixed is normal. For them, there's always an ease in understanding that I can be simultaneously many things and one thing at the same time. They don't ask where I'm from, they ask who I am. There's something beautiful in that.

I spend a lot of my life explaining my existence. I often feel myself inwardly sighing as I approach the topic of my mixed identity in a conversation, not resenting it, but just secretly hoping it doesn't get spun out into something bigger than I want it to be. Other times, I delight in sharing my mixed heritage, proud of the fact that I represent something special, something previously taboo, something which exists as a testament to the power of love to cross cultural borders. But it's still explaining. I used to feel an intense envy towards people who were allowed to gracefully side step the ‘where are you from?’ question. Now I've mellowed out, but I do find myself biting my tongue every now and again.

More than anything, I feel like I'm constantly fighting to maintain my status as a person of colour. As a mixed-race person, I experience racism. But I've come across people from a multitude of cultural backgrounds who desperately want to belittle my experience of it. Many of those people are White, but certainly not all of them. I deal with many people of colour who see the white part of my identity as something I ought to be ashamed of. And, in a way, I get their perspective. Colourism is alive and growing in communities of colour. But I'm aware of the privilege that I'm afforded within my community as well as outside of it. I rarely experience explicit racism, say, in the form of violence. But every time I've seen it, I've intervened. I've protested against racism. I've fought for racial equality for those in my community who have it much tougher than me. I despair how my Black, or Asian, or Middle Eastern friends are treated, and I try to use my privilege to support them. When I experience racism though, I'm sometimes asked by friends of colour to 'prove' that it's really racism or met with skepticism. And that hurts.

I do think there are bias attitudes & stereotypes towards mixed-race people, but it's complicated. I'm told that I'm ‘exotic’, something which doesn't sound particularly negative until you begin to unpack the sentiment that it's trying to convey. I'm often told (more often, shown) that I'm not allowed to operate as a fully-fledged member of either of the cultures that make up my parentage. And I think many people of colour see mixed-race people as invalid - like we don't have an inherent understanding of the experience of a Black person, an Asian person, or a Hispanic person. And they're not entirely wrong - but I do think as a community we need to spend more time reminding ourselves that we have much more in common than we have apart. We don't exist in opposition to whiteness - people of colour are their own gloriously diverse group, but even though we're divided by language and cultural custom, we're united by our history.

There's also the stereotype that we're beautiful - and so long as it's not explicitly fetishing, I don't actually mind that one.

I am obsessed with languages, to the point that I even studied them at university and travelled the world trying to learn as many as possible. But I was never taught Tamil, my father never deemed it useful to us, and considering that my mum wasn't able to speak it, I think he decided that the best thing to do would for us to grow up speaking solely English.

Not speaking Tamil doesn't affect me in any discernible way. My father isn't involved in the Tamil community in Sydney and it's actually very novel for me to hear him speak it. I delight in it, every time I hear him speak Tamil it awakens a part of my heritage that I'm so desperate to connect with. And eventually I will.

Ultimately, I feel Australian. I grew up in Australia, I have a (slowly anglicising - eek!) Australian accent. My cultural reference points are markedly Australian, and I still find the London winter to be abominable. The experience of living in the UK has been important in allowing me to demarcate British culture from Australian culture and has probably led me to cling onto my Australianness as I'm confronted by the cultural quirks all around me.

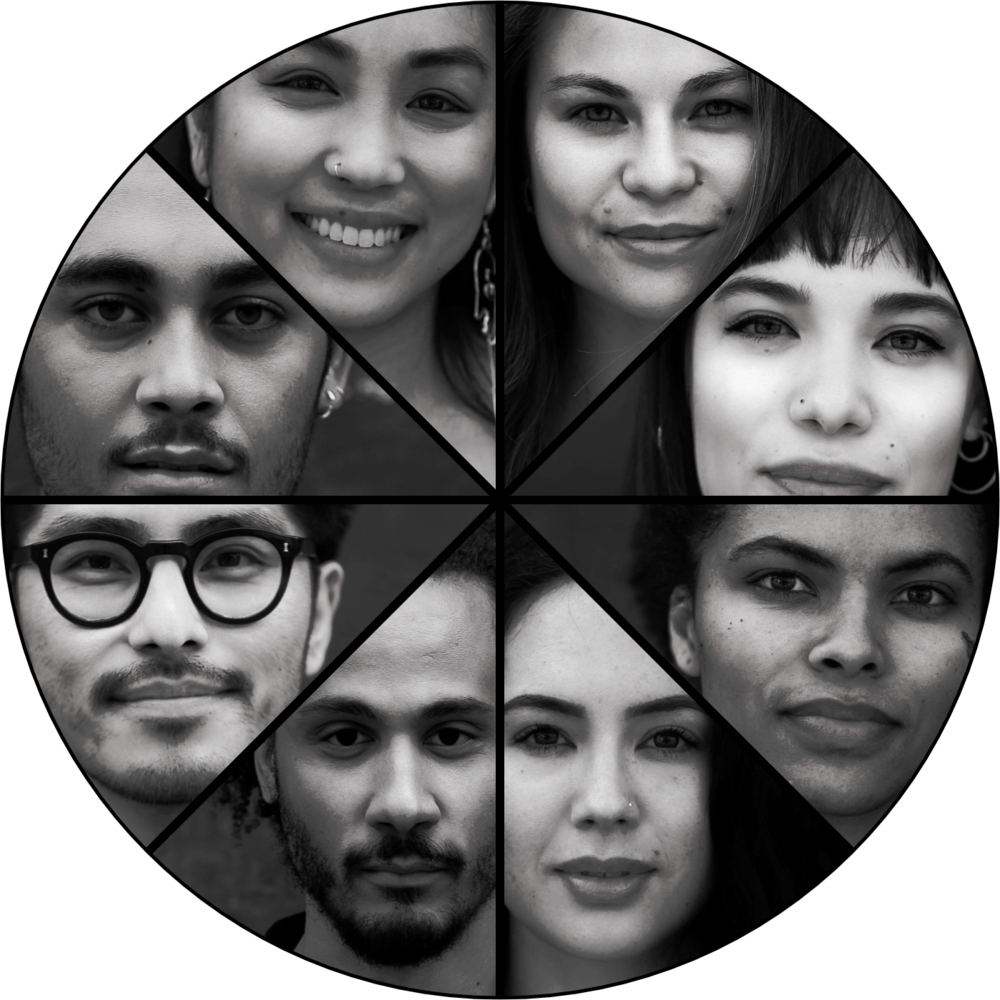

More than anything, I've made a conscious decision to try and make being mixed-race its own cultural touchpoint. I want being mixed to be its own category, that co-exists alongside all of our cultural backgrounds, without encroaching on their space. In a way, I see being mixed as its own kind of 'culture'. As a subset of people, we have so much in common, so much to communally celebrate. So many of us have felt the same feelings at similar times in our life. I'm really thankful to live in a world where a project like this, which is unashamed in its celebration of mixed-race people, not only exists, but is thriving. We are a big part of the future, it's about time people started to see us for who we are - people whose existence continues to be revolutionary.

When people ask where I’m from I usually reply sarcastically, unless I'm feeling particularly kind. I always respond that I'm from Australia and lob the ball back into the court of the person asking. It's almost a test – will they dig deeper, do they really think my cultural background is of paramount importance to our continued interaction, or will they let it go, and perhaps just ask me how my day is going? It's always interesting to see what happens.

I think the experience of constantly not belonging has been both positive & negative. In my formative years, it was a source of incredible difficulty, making me wonder whether I'd ever find people like me who existed in the spaces between labels. But it's also been an enormous positive. Had I not felt so acutely isolated, I'm not sure I ever would have taken my identity as a mixed-race person by the horns, ran with it, and come into my own. I now talk openly, and proudly about my mixed heritage, basically to anyone that will hear. I am supremely proud of the person who I am today - but I could have not gotten there without once experiencing self-doubt.

Being mixed in today’s society is getting better, it has been getting incrementally better as we as a society eschew our biases and strive to find our commonalities. I think being mixed-race is still revolutionary - it's a sign of a globalising world in which two people looked past race, ethnic background, language & culture and entered into loving union and produced offspring. We are symbols of unity. Symbols of shared humanity - it's beautiful! The next step is for us as a community of mixed-race people to find friends and confidantes in each other, recognise that we do belong, and that all the growing pains associated with having a 'mixed' identity have just been part of becoming the new normal.

If I had the opportunity to be reborn I'd return as myself, every single time. I am who I am because of the difficulties I've faced. I wouldn't ever seek to change that.